In sultry Salvador, Brazil’s first capital and third largest city, the vast majority of social life – and socializing – takes place in the streets. Bars and restaurants spill onto sidewalks. Samba jams, pocket shows and mega concerts erupt in squares, parks, and on beaches. Then there’s the city’s legendary Carnaval; it’s billed by the Guinness Book of Records as the largest street party on the planet.

In light of this alfresco state of being, it’s not surprising that Salvador has one of Brazil’s most original and appetizing street food scenes.

Bahian street treats

In Salvador, street eats begin at dawn with local women who fuel workers with rice, tapioca and creamy corn mingau (porridge), spiked with cloves and dusted with cinnamon.

Bolinhos de estudante

As the morning progresses, in front of schools and university campuses, students line up to get their sugar fix with bolinhos de estudante. Named in their honor (“student balls”), these deep-fried treats owe their chewy consistency to tapioca flour mixed with coconut milk.

Meanwhile, those with leisure time on their hands can head to one the city’s myriad beaches where vendors, armed with tin can barbecues, grill skewers of queijo coalho. This tangy regional cheese is particularly addictive when doused in oregano and sugar cane molasses.

Salvador’s street food scene gathers additional heat, and spice, in the late afternoon, with the release of workers from jobs and kids from school, and the lengthening of shadows on the beach. Suddenly, the air is infused with the heady fragrance of dendê oil – a distinctively pungent smell that is the perfume of Salvador.

Salvador’s favorite “fast food”

Acarajé

The scent of dendê – a species of palm that grows along the coast of Bahia and whose fruits are pressed into oil – is the calling card of acarajé, Salvador’s most iconic and ubiquitous “fast food”. Basically defined, acarajés are tennis ball-sized fritters made from a puree of black-eyed peas that are deep fried – until crisp (on the outside), but fluffy (on the inside) – in crater-sized pots of sizzling orange dendê oil. And that’s just the beginning.

Once cooked, acarajés are split open and then comes the fun part – filling them up. Choices include one or all of the following: Vatapá, a thick paste dominated by cashews, shrimp, ginger and coconut milk; Caruru, a puree of diced okra; and Salada, in which finely diced tomatoes are seasoned with onions and cilantro. For an extra real or two, you’ll be blessed with a bonus serving of glistening pink-orange camarão seco, dried shrimp whose salty bite adds an oceanic twist to the proceedings.

If you want your acarajé with all the trimmings, ask for a “completo.” Those who like it hot, and put in a request for “quente,” will receive a generous smear of fiery pimenta (malagueta pepper) sauce. Gringos with heat sensitivity issues should make sure their acarajé is served “frio.”

An edible heritage

Baianas

Like much of Salvador’s distinctive local cuisine, acarajés originated in Western Africa where they were known as akara, which in Yoruba translates into “ball of fire.” The recipe crossed the Atlantic with the hundreds of thousands of slaves shipped to work Brazil’s colonial sugar plantations.

To this day, acarajés are among many sacred foods eaten during Afro-Brazilian Candomblé ceremonies and presented as offerings to the divinities known as orixás. In fact, many Afro-Bahian women who prepare acarajés on street corners throughout the city are followers of Candomblé. In keeping with tradition, “baianas” are often clad in the white turbans, voluminous hoop skirts, glass beads and bangles worn by mães de santos, or priestesses.

As symbols of Bahian culture and identity, baianas have a memorial-museum dedicated to them in the historic Pelourinho district as well as an official day of commemoration on November 25. In 2012, the state government of Bahia declared baianas de acarajé as intangible cultural heritage.

Best of baianas

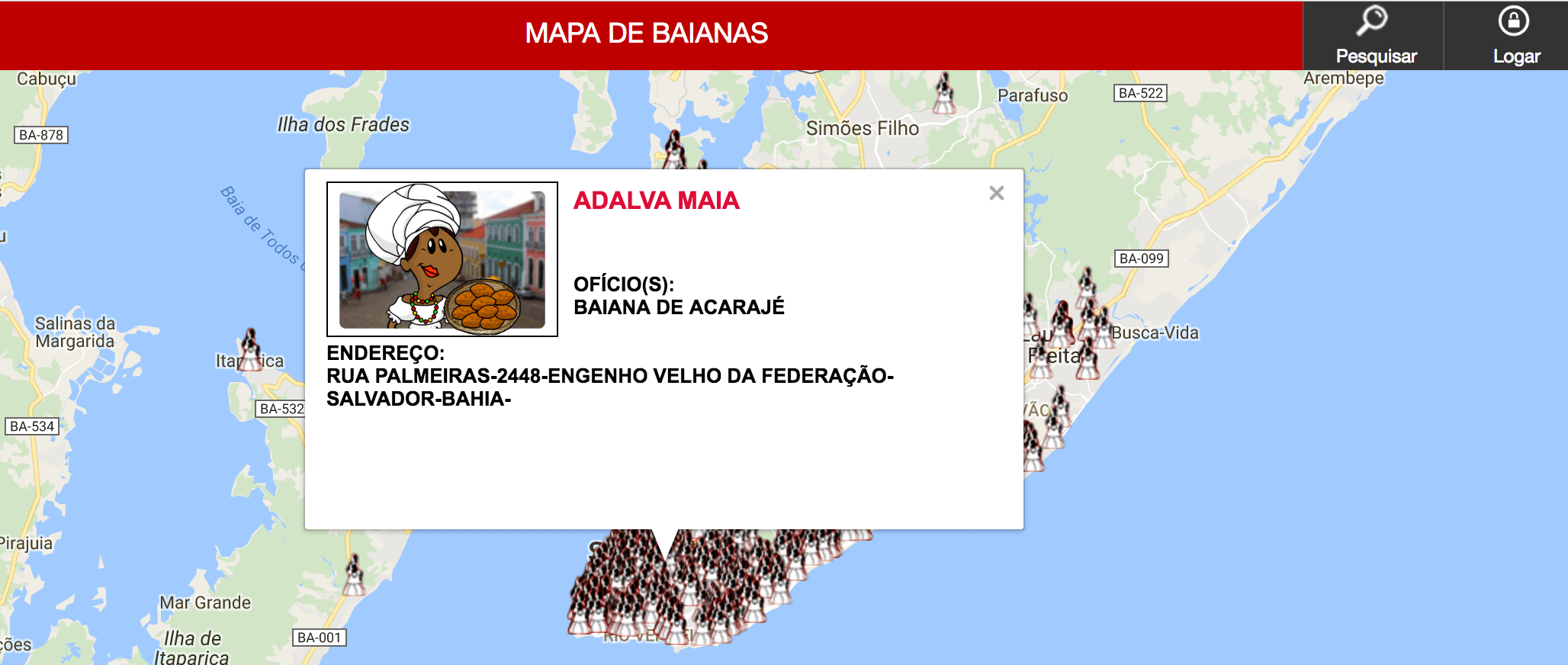

Oyá Digital’s map of baianas

There are an estimated 4,000 baianas scattered throughout Salvador, all of whom can be digitally located via the Map of Baianas published on oyadigital.com. A handful of these women have become local legends, whose fritter-frying renown has earned them national fame and considerable fortunes. For years now, the reigning triumvirate of baianas has been Dinha, Regina and Cira. All three hold court on outdoor squares in Salvador’s bohemian beachfront hood of Rio Vermelho.

Meanwhile, most Salvador residents have their own favorite (more affordable) baianas to whom they are faithful. My own predilections include Neinha, located on a corner of Centro’s main street of Avenida Sete de Setembro, and Luiz, a rare male baiano who has a loyal following in the historic neighborhood of Mouraria.

Located on a leafy cobblestoned street, Luiz’s ponto is outfitted with plastic chairs and a wide-screen TV. This set-up allows customers to watch snatches of a soccer game, or the latest political scandal, while chasing their acarajé with an icy beer, or – better yet – a chilled can of Coke (the cola’s sweetness plays surprisingly well off the spice and salt of the acarajé).

Acarajés get a lot of love – and press. However, most baianas also serve equally enticing, yet mysteriously unsung abarás, made of pureed black-eyed peas that are boiled instead of deep fried. After being mashed, the thick bean paste is densely packed and then elegantly wrapped in banana leaves to seal in the moisture. The resulting taste sensation skews smooth and silky and is more delicate than acarajé. Happily, all the same delicious fillings apply.

Abarás